' The erthe in oon is ever prest,

Now bedropped, now all drye;

But uche gome glit forth as a gest:

This world fareth as a fantasye. '

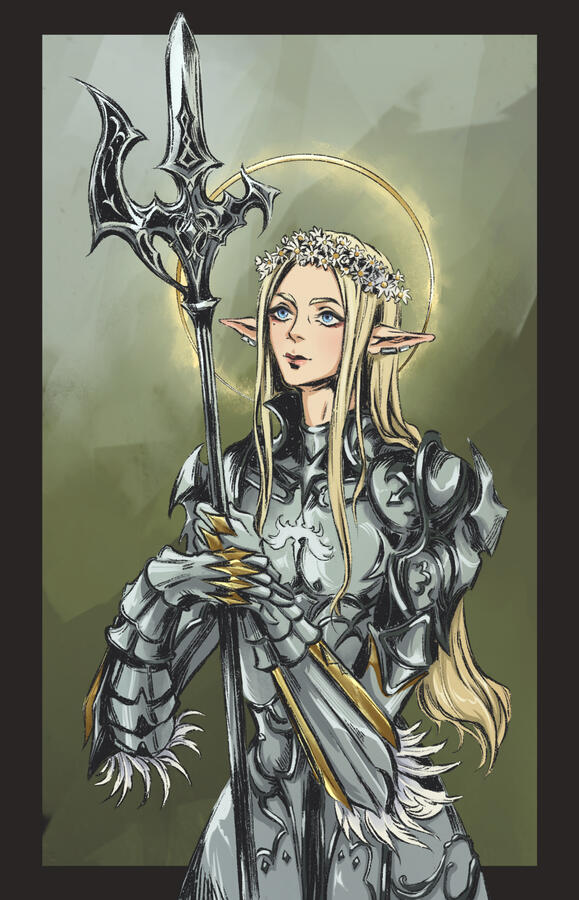

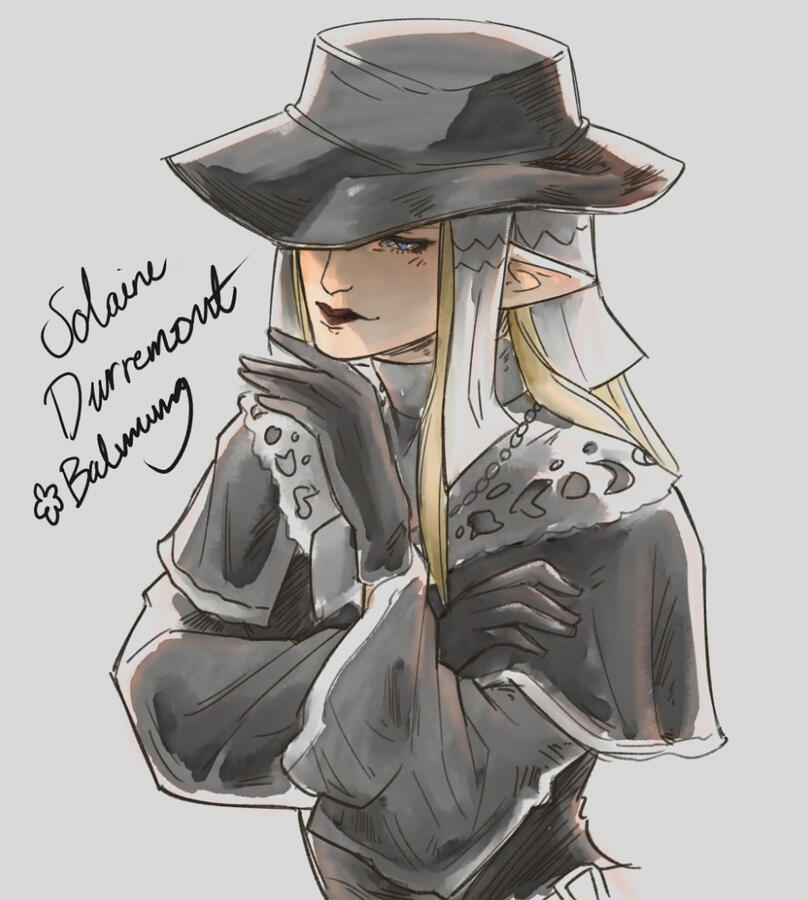

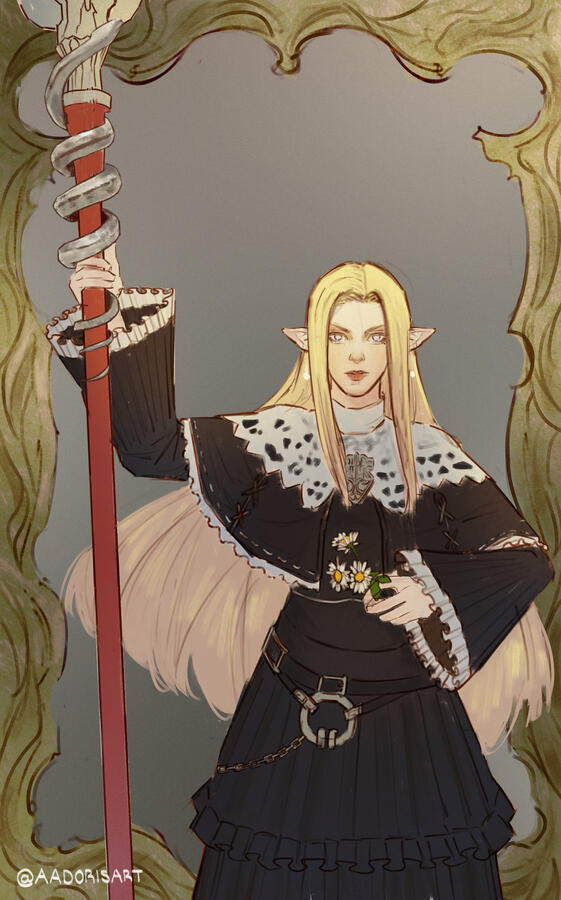

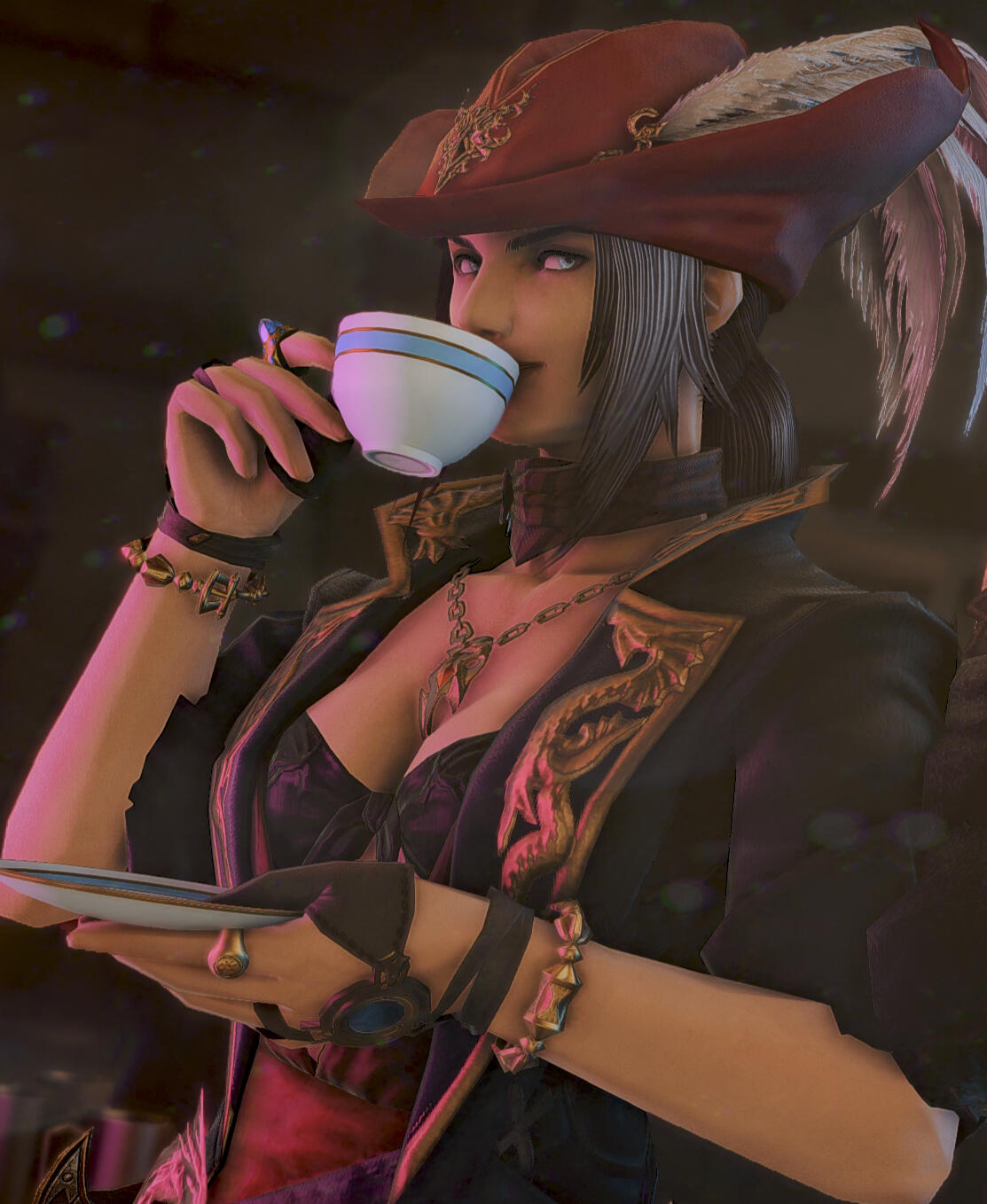

Solaine Durremont

| AGE | ~ 36 |

| RACE|ETHNICITY | Elezen|Wildwood |

| GENDER | Female (She/her) |

| NAMEDAY | 10th Sun of the 1st Astral Moon |

| PATRON GOD | Halone, the Fury |

| PATRON SAINT | Camille de Lisieux, the 'Little Daisy' |

| HEIGHT | 78 ilms |

| OCCUPATION | Traveling Lancer |

| FORMER OCCUPATION | Inquisitor; school-teacher |

| ORIENTATION | Aromantic and pansexual |

| RESIDENCE | ????? |

| STEED | "Arbiter" (Dravanian chocobo) |

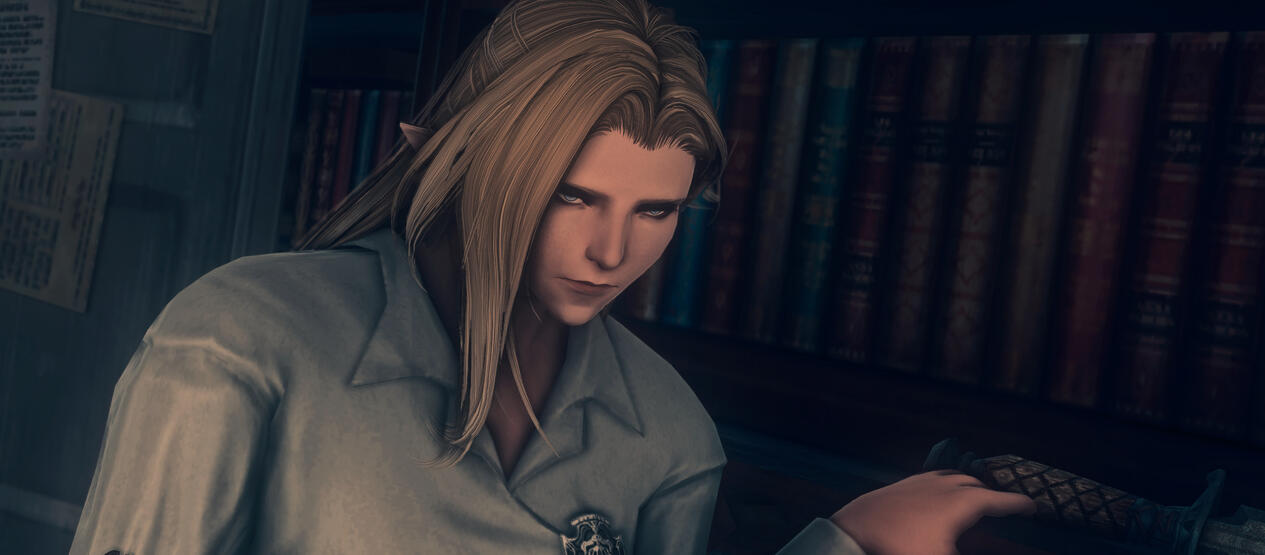

There stands Solaine by the table-head, pale and ceramic as a vase of lilies. When addressed, she replies coolly in a contralto voice; conversations and exchanges reveal that she is learned—perhaps considerably so—and polite, if not a little frosty. A crisp, tidy bob of gold hair hangs above her shoulders, framing tapered ears and an angular face. She is tall, straight-backed, an obelisk whether armorclad or draped in a penitent's black. Her red mouth forms a thin smile that just barely reaches her eyes.Those eyes. They are sleek, shaded, and thickly lashed; at every angle or glance, they seem distinctly feminine. But they pierce when they look, with a sharpness that lingers. Their hue is memorable: a hard, crystalline blue. These are striking eyes, unsettling ones. They are eyes that scrutinize everything.

FFXIV Write - 2022

I. CROSS

An excerpt from Too Few Loaves and Fishes

a storyline set during the events of Heavensward

“I am sorry,” the weary warrior said as he pressed the rosary into her wind-chapped hands. “I am sorry the world unto thee hath been cruel. Thou wert borne along in lovelessness, and in thy tender days knew neither mercy nor care. I am sorry for thy endurance, bereft of it. It is a travesty that you must rise, and be, and end each day as thou art.”She looked down at the rosary. Immediately she knew he had made it: the beads were rosewood, whittled by a chiseling knife. He must have done it in secret, she thought, before dawn or after the Convictory camps bedded down for dusk. She searched her memory of the past two miserable moons, and could not place any moment where she’d seen him toiling with his awl and file.“I do not want it,” said Solaine–harsh at first, but then, tight-throated, hating her harshness: “I do not want your pity.”“I clepe nonesuch to thee.”“Then what?”“A gift,” he said, urging the rosary firmly into her hands. “Thy faith is thine mainstay, is it not? Permit me this grace. I have naught to give thee, mademoiselle, but my sentiment and yon garland-and-cross. Wouldst thou take it?” He spoke so gently that it unnerved her; she had never heard his voice without its hard, gravel tone. “Truly, I am sorry. A more courteous life hast thou deserved, and a greener one besides.”He let go of her. Slowly, nervously–as if she feared unraveling the beadwork–Solaine ran her hands along the rosary. She counted the cords, the spears, the bold wooden ‘X’ at the nape of the loop. He had made it to Orthodox standard, perfectly braided: there lay the requisite thirty-three knots.She wrapped the rosary around her hand. The beads dug hard into her cold, pale fingers.“Thank you, sir,” she said. “Pray with me, then. I implore you.”They bowed their heads. Outside, the wind roared across the Convictory, battering snow against the wagon panes. But once they began the O Fury, they could not be interrupted. They did not pause until the prayer concluded, when their numb fingers climbed to the next carved bead.

III. TEMPER

three times rage wet the whetstone, for weal or for woecontent warnings: violence, harm/distress to children, upsetting religious themes, descriptions of torture/physical harm and choking/strangulation(please heed the content warnings; I insist you do not continue reading if you’re sensitive to dark themes/fictitious content)

“It broke,” said the child, holding up the pieces of the red clay bust of St. Reinette in her outstretched hands. “It fell on the floor.”“I saw you,” said the lady. She had been in the room when it happened, cornered with the red drapes and the harpsichord; now she was big and furious in the room’s center, filling it up with her rage. “I watched you pick it up and toss it!”The child scowled. She glared at the chunks left on the floor. “It broke when it fell.”“It fell when you threw it,” the lady replied, waving a chunk of St. Reinette’s big, holy nose. “What in all the heavens has possessed you? Who in all the saints do you think you are? You little beast.”The question burned in the child’s ears. This lady, this tight crimson string of a woman, had wound herself around every hall of the lord’s manor like a choking vine. But she couldn’t beat her anymore, not after the lord’s recent edict. The rod was no longer necessary, not for dour little Solaine. Scripture was a far better adjustment for the hideous moods of youth.The words came out, unfettered. “I am Her holy penitent,” said the child, half-shouting, her throat hurting. “I am a gelid spear. I–”The lady swatted her above the ear. Tumbling out of the child’s hands, the coppery pieces of St. Reinette’s face made musical sounds against the marble floor.- — -The prisoner was crying. This was not noteworthy: the floors of the Tribunal gaols were often wet from tears.“And piss,” the warden muttered, handing a leather smock over to Durremont. “We cleaned it up already, but she soiled herself. The inquisitor they sent before you was a smidge rough.”“What did he do?”“Told her what he did to her husband,” said the warden. “Showed him the cut fingers. A real mess, if you ask me, mademoiselle, but what do I know?”Frowning, Durremont strapped the smock over her black-and-blue robes. She adjusted her wimple, her rapier belt, the missal girdled around her waist by delicate chains. The silver aspergillum clinked as she felt for her missal’s leather bindings. She did not like to attend even informal interrogations without Her holy word close by.“You know plenty,” she told the warden before he stepped back and let her in the cell.Inside, the prisoner sat up. She stared up at Durremont with wide, rheumy eyes.“A nun,” she whispered. “They have shown m-mercy?”Durremont did not reply. She took the aspergillum from its chain and flicked it once, twice, three times over the prisoner’s head. When the holy water touched her scalp, she began to scream.“Sacred Fury, Heavenly spear, we pray this hour unto thee–”Wailing, the prisoner rushed her. The impact was unbelievable: She was not a big woman, but terror made her strong. Durremont watched the ceiling spin above her, whirling, transforming as she tumbled to the hay-strewn floor. Pain streaked up her neck. She could no longer breathe. Above, the warden was shouting, the straw rustling, the girdle chains chiming like a thousand tiny bells. The prisoner roiled above her, pulling something tight with her filthy hands.“Get her off!” the warden was crying. “You there! Grab her arms, quick!”The prisoner yanked away. Again the room was spinning: strong arms were pulling Durremont up from the stinking straw. A guard spoke in her numb ear, pressing something into her shaking hand. The silver chains.“You mustn’t wear these,” the warden urged–later, in the rectory, after they’d locked the prisoner back in the cell. “It is too dangerous, mademoiselle. What if we had not been there? She had them twice-looped around your neck.”She gave the chains to Inquisitor Amorevain, who eyed her scrutinizingly, conspiringly. Durremont had been overbearing, nigh cruel towards him when they studied together at St. Endalim’s. His shrewd face spoke plainly: surely this gift was some kind of trick.“Flattery,” he said, “is ugly on you, Solaine. You have never given me presents before.”She rubbed her neck. The wimple was unbearably itchy, but she dared not remove it. She did not want Amorevain to see the marks.“I shan't do it again,” she said hoarsely, leaving him standing in the Tribunal offices with the silver glinting in his gloved hands.- — -The burdock was blooming. All around the Black Boar Gate, dense clusters of spiky pink flowers nodded their heads in the breeze.“Ow!” yelped Solaine, yanking back her hand. “What in the gelid hell?”Mathilde’s dark head popped up from behind a bush. “What happened?”“They have thorns!”“No, they don’t.” Laughing–looking guilty for having laughed–Mathilde rounded the shrub with her basket on her aproned hip. “You must’ve picked the wrong thing.”“I did not–burdock leaf looks like a heart, right?”“Aye.”Solaine shoved her finger in her mouth. “Maybe it was a wespe.”“Here, let me see?”“No.” Sulking, Solaine reached for her own basket. “Don’t fuss over me.”“Fine, bitch. Be stung.” Mathilde goosed her side and dodged a playful swat from the taller woman. They both laughed, the prick forgotten. Soon they settled back into the routine of plucking the heart-shaped leaves. It was summer in the Shroud, and the afternoon sun poured thick, liquid-gold light through the overhanging leaves. For a peaceful hour the two women had been gathering herbs for Guild poultices, and their only other companions were a family of dwarf rabbits that grazed on the burdock nearby.“When I was little,” Mathilde said, shredding a dandelion, “my father would go to work, and leave me in the care of my cousines. This one, we called him ‘Big Tristaine,’ he was taller than all the girls and me. Would you believe this–he had a pet wespe?”“Mm. How’d he manage that?”“He tamed it somehow. It used to sleep up in the eave at night, and come down in the morning all buzzy-buzz. He’d feed it honey and gristle. Can you believe?”Solaine took a trowel out from her basket and began to dig for burdock root. “Did it ever sting you?”“No. It used to chase my dog, though. The one I told you about, little Jo.”“Aye.” With her back turned to hide her smile, Solaine troweled the soil to loosen the root’s stubborn tendrils. That season there had been many stories about Jo.Mathilde sat back on her knees. She peered at Solaine’s shoulders, where the dense, pale coil of her braid hugged her nape. Then she looked around, searching; a wren was scolding the rabbits as they nibbled in the grass. They were truly alone here, no apprentices or eavesdroppers. She breathed in deep, and steeled herself. It was time to try asking again.“What about you?” she put forward carefully. “Did you have pets, as a girl?”Solaine did not answer. Her trowel went hack, hack against the root, as if chopping it. She stopped to wave away a fly.“No,” she said finally–taking so long to reply that Mathilde already regretted asking. “My father wouldn’t allow it.”“Why not?”“It went against his beliefs.”“What d’you mean?Solaine jammed the trowel against the root. She almost had it out. “He often said it was wrong.”Mathilde made a face. “How’s having a pet wrong?”“He said it spoke poorly of one’s character. And he was right.” Tersely she added, “it is immoral to claim ownership over anything that lives.”Mathilde rolled her eyes. With Solaine, there was so little reciprocating, be it with smiles or kindnesses or even idle stories. And the religious stuff: Gods, there was no end to it. Mathilde had never been to Ishgard, had never wanted to. A decent person would hear Solaine talk about it and think it was one of the seven hells.Solaine spoke up. “It may seem strange to you,” she said, “but that was just his way. It was his nature.”Mathilde scoffed. “Sounds like his nature was shit.”Whack! With an angry grunt, Solaine flung the trowel across the grass. The rabbits scattered; overhead, the wren blinked away behind an elm. Mathilde shot up with a huff. She slapped her aproned lap.“Oh, alright,” she cried. “Toss your things around, will you! You big baby.”She went to pick up the trowel, but Solaine caught her by the wrist. Mathilde stared up at the taller Elezen, whose pale face was pinched with remorse.A surprise: Solaine was apologizing. “I am sorry,” she muttered, taking Mathilde’s hand. “I should not have thrown it.”“Damn right, you shouldn’t have. Gods, I swear.” Blushing, she gave Solaine a small shove of forgiveness. “Sometimes you’re such a child.”They looked for the thrown trowel. Mathilde found it first: it lay in the grass beside a huddling rabbit. At first they wondered it had been struck by the trowel, but then it hopped and sniffed; it seemed unharmed. It peered up at them curiously, wiggling its wide pink nose.It followed them back the Lancers' Guild, where they brought it a dish of lettuce. At first, Solaine refused to name it, but after they found it napping splay-legged under a training shield Mathilde wrung her arm until she caved."'Grumpy,'" she said flatly, tucking a lock of hair behind Mathilde's long ear. "That is its name. Are you happy now?"

IV. EIDOLON (choose your own prompt)

a glimpse into a dark place, where someone waits, impatientlycw: violence, mild gore, themes of torture, themes of disassociative/disorienting reality

Unfortunately, he was dead long before she killed him. This was a simple truth. The wraith-knight pondered this as he stood in the old cathedral, the light of sunset kaleidoscoping through the saints entombed in stained glass: you couldn’t call it ‘living,’ what either of them had gotten up to when he was alive.He peered up into the rafters. Six round, lustrous pigeons murmured in the eaves. The cathedral towered around him, a deep-chested cave of Coerthan stone. He inspected its slopes, its mullions and transoms, the places where its weighty timbers dovetailed together below the pitch. Everything lay in its place. Even the great statue of Halone the Fury, her hoplon blazing and her spear aloft, seemed at peace looming above her altar. These birds were supposed to be there, and that relaxed him. None were ripping out and eating his liver today.The statue held a clump of marble daisies. He watched them bloom bone-white in the Fury's crushing hand. For a moment, he could not remember his name.Like Halone, like hierophant, like hail and hallelujah, he knew it began with an 'H.'It was not always like this. Another simple truth: she was terrible at upkeep, and often he found the cathedral in ruins. Yestersun she blew off the roof, spraying chunks and mortar across the fields for half a malm. He had loped out of the narthex to avoid falling rocks, only to stumble onto spears of stained-glass sharding out of the surrounding field. They were bright and vibrant and slicing, like rainbow needles. He had scowled up at her white sky (the most opaque and frigid white, a sign she was truly furious) and scolded her, chiding her for lack of restraint. Enraged, she had turned the field into a roiling dune.“Quicksand is a myth, inquisitor,” he’d shouted as the drifts swallowed him whole. “Nobody actually drowns in it!” Gasping for air, just before a shard spiraled by and sliced open his jugular: “You read too fucking much!”But that was yestersun. Today, the windows glowed like polychrome haloes; she had illuminated each saint in carmine and lavender, teal and umber and delicious burnt orange. A new detail, one that surprised him: she had lavished their feet with blades of uproarious green.Distantly an organ played. The wraith-knight did not recognize the song. He waited for the sound of footfalls, breathing, a pattering of faraway voices. Three flies buzzed around his ruddy brow.Do you know, he thought, another word that begins with 'H,' inquisitor?Music, though: he did miss this, now that it was over. He closed his eyes and tried to remember. One of the Tribunal acolytes had been a soprano, her voice gentle as a lark. Couldn't sing worth shit after he'd slit her throat, but that didn't matter. And then there was the inquisitor he'd tracked all the way to Black Brush, who had a little skill with a harp. He had forgotten the man's name, and that mattered even less; the fool died without a jaw, so what use would he have for a name?A cleaner memory came back. On evenings like this his brother played the harpsichord with the windows open and the curtains drawn. It bothered him immensely that he could not remember the hue of the curtains, which, in his memory, were always red. Like blood, like apples, like his hair: all of these were wrong. In life, the curtains had been some other color entirely. He was sure of this.Behind him, a stone fell in the nave, clattering as if tumbling down a deep, lightless well.She would not come today. This he knew in a flash of understanding: up above, in the world of the living, she had been given something to do. A novel carriere, a compulsory task. Anger pulsed through him as the cathedral spoke silently: She was meeting that witch. A stupid distraction, he told the cathedral directly. He had a terribly funny joke to tell her before she killed him again.Now the daisies were gone. The statue wept tar, and from its chiseled spine had sprouted a pair of wide, incongruously feathered wings. Above, the pigeons flapped. Crimson light sliced in from a western window, as if unstoppered from a passing cloud. He watched the light spread across the aisle, cutting the pews, sweeping the wool aisle runner like the edge of a slow, red knife. None of this was his doing, but the cathedral whispered that no one else could be more at fault.Hell, thought the wraith-knight–you are so correct, inquisitor. The word that begins with 'H.' Clap, if you please.He tried to cross the aisle. The pews stunk of musty wood. His greaves strained, but the soles wouldn't budge. He sighed.Blue gripped him like a fist, white-knuckled. Suddenly he was sure the brother's curtains had been some shade of blue.So he stayed there. A dark, furtive force kept him planted firmly on the stone, and though he would have loved to step closer and see what else she had hidden in the glass he could not move. That was more a punishment than dying, honestly–this understanding that he was stuck here for who knew how long. He would've liked an opportunity to doff his armor, set down his greatsword, and truly prepare for her: to reconnoiter this vast, holy cavern and root out some needful granule of information that would prepare him for what might come.But not today. The wraith-knight accepted that. He could wait.He was down here and dead, and that suited him. Better than being out there with her, unfortunately alive.

"Wars are lamentable things," said Lord Fabian de Courcellaine, on the frigid winter day he took the girl from the Forelands homestead. She clutched bluish fingers around the hem of his coat; she was five summers old, lean and hungry, a wood-wild weed. He knew he could correct this. With the same hand that signed the execution order for the heretic mother, he pinched the child's chin between thumb and forefinger. He peered into her watery eyes. The lord-inquisitor sensed a mote of sympathy, genuine if not a little glib: "I suppose this makes us two lamentable persons, does it not, Solaine?"He took her away. Across snowy roads, over Coerthan hills mottled with winter sedge; beneath the stone towers and terraces of a city the color of a full moon; they rode. The old capitol was overwhelmingly new. Solaine had never smelled busy streets, good leather, tired chocobos. At the manor's mouth she met Marguerite de Courcellaine, unsmiling elder sister to the lord-inquisitor. As she stood in the sober parlor of the drafty red chateau, she thought of the heretic mother, who had teemed with witch-tales, folk stories cloyed with ghosts and curses and black claws at night. Lady Courcellaine would come to embody all three.So, there was a wardship: those dark, haggard summers in the stories where the orphan either sinks or swims. In Solaine, the lord-inquisitor found a pleasing malleability, an aptitude towards study, scruples, and the faith that might have saved her mother. But he also found rage, a volatility in the girl's mood that frightened everyone who witnessed. Books were flung. Teeth were cracked. The cook lost a finger and the governess quit in sobs. Then the maid discovered a steel spear-head snuck and hidden under Solaine's mattress. The Madame had no choice but to haul her by the scruff and drop her at the lord's unyielding heel. "My sister thought to break you," sighed Lord Courcellaine as he signed the grim papers stamped with St. Endalim's badge. "But as she cannot, by the Fury—mayhap the Scholasticate will make of you something more."

What does it mean, to be broken? Through a miserable adolescence, the mademoiselle pondered this: at bedtime prayer; before thin, oniony meals in St. Endalim's mess hall; during mass, vigils, and weeknight vespers; while supplicating through a seven-day fast in honor of St. Camille de Lisieux, blessed 'Little Daisy' of Halone. When would it happen? What part would break first? The spirit, surely—or (as she worried the scars from Courcellaine's nails) first a pound of flesh? Only Halone could judge. Prostrate before Her statues, staring reverently through somnambulist eyes, Solaine beseeched her goddess to hone her rage to a needle-point. Prayers became answers. Soon she was selected for inquisitorial study at the Tribunal. Gone were the sleepy Scholasticate libraries, abandoned for the bowels of the Tribunal hall. So began the timeless duty: locating, correcting, and chastising Ishgardian heretics. Judging them and finding them wanting, putting them to rest and ending their spiritual dearth. Dogma begat doctrine, doctrine begat ritual, et cetera, de integro. Who beamed more proudly on the day of her initiation rite: the girl, or—bearing witness nearby, grinning, his teeth white and sharp—the lord-inquisitor?Summers passed. The dragon-battles raged. On a bloodless spring night, Lady Courcellaine died in the red chateau, her hands cradling a rosary. An admission of heresy lay tucked in her Enchiridion, signed in a florid hand. Inquisitor Durremont said a psalm for her soul and departed the next morning to rout blasphemers hiding near Gorgagne. "I grieve not," she told her colleagues, riding away from the graveyard with dry eyes. "To mourn the unclean is to tarry, and we have other funeral rites to dispense."

Everyone knows the next part: And then, it all ended. The chapter closes and everything routs. Amid crowds of the faithful—beneath the leathery wings of an enemy that defined an age—the war closed in ceasefire in the capitol. What now? The inquisitors: What was to be done? How should the Holy See handle their holy killers, now that they'd sanctified their former prey? Options were indexed. Plans were crafted; deliberations were made; most fell apart, fragile as scholar's parchment.To Solaine, the future—like her faith—was non-negotiable. Outraged at doctrinal changes, she spoke out. Few listened. When words failed, rage put a blade in her hands: At morning prayer, she brought her dissenters to their knees. Some say it took five men to subdue her and fetter her in irons.Trials followed. She fell ill during a series of confessionals. There was an agonizing summer in a Tribunal gaol. They cannot break me, thought Solaine, prone and bleeding in her cell, her chapped fingers worrying over a wilted missal. The histories claimed that St. Lisieux the Little Daisy once kept vigil until she wept blood. So, Solaine endured. What trial could they impose that the most faithful could not withstand?Then came Lord Fabian de Courcellaine to deliver the surprising news of mercy. How strange—the way he towered in front of her cell, reached through the bars, and cupped her filthy chin in his pale, clean hand. He smiled as he spoke, his tone gentle and his face soft. The way her eyes glistened, one would think she'd seen divine grace.A second chance, declared Fabian as they rode out of Dragonhead. The Shroud—ah, only some malms further. 'tis safer than the capitol, for one there knows you. We deserve this, Solaine. A chance to be less lamentable people, you and I.Riding behind him, Solaine watched his throat, the neck-cords that bobbed as he spoke. I agree, she murmured. Only a little further. He did not know how right he was. He did not know about the spear-head, hidden in her sleeve, and how much it agreed with him, too.

So, what after? Where did she go, emancipated in that long year of exile? A rumor here, a sighting there, hearsay after hearsay until the old names evanesced into ghosts. Durremont remained a daughter of Ishgard—but what Ishgard remained for her, few could say. Who cared enough to know?There's a truth about weapons: that a blade performs the same whether welded in a hilt or to a ploughshare. You can repurpose a weapon. Rinse them of blood, melt it to slag, reforge it into something useful and tame. You can do this. Many will try.I did try, thought the lord inquisitor, lying in a snow drift, bleeding out from the spear-head's wound in his neck. It was the last lie he told himself, and maybe it gave a final comfort: Fury forgive me, I had no choice. There was a war...He could not remember the war. He died thinking of the Foreland homestead and the inquisitor's gibbet, where the pale-eyed girl stood with witch fingers tugging his hem. The fresh snow piled on silvery weeds. Such lamentable things.

THE LORD F. DE COURCELLAINE

A CRUEL GENESIS: many an Ishgardian's fate would be very different had some shrewd, amoral inquisitor kept their ambitions in check. The lordling "FABIAN" once dreamed of life as an architect, a future squandered by his sire's gambling debts and skipped tithes. As a young inquisitor, Lord de Courcellaine dispatched a Forelands midwife under suspicions of heretical witchcraft. He installed her young daughter Solaine as a ward in his household, viewing her as a challenging project: could he, ever the architect, build the most devout of apprentices from a wood-heathen's get? For some twenty-odd summers, his aims bore fruit—only to crumble at the close of the Dragonsong War, when an overzealous Solaine was imprisoned for the killings of three reformist clergymen. Forsaking his tenure to lessen her charges, he departed with her in exile from Ishgard, only to be found dead in the Coerthan snowfields a sennight after paying her bond. May the Fury weigh his errant soul.

M. DE COURCELLAINE

AN ARBITER: oft referred to as simply "MARGOT", this veiled sorceress is the dragon-worshipping younger sister to the late Fabian and Marguerite. Cast out of the family not long after her sixteenth nameday, Margot fled Ishgard and installed herself amidst heretic covens to surreptitiously plot against her religious, power-hungry siblings. Durremont regards her as both teacher and ersatz kindred: a keeper of legacies, alluring secrets, and some of Eorzea's more unpleasant truths. While the two have not spoken in some time, Solaine is at leisure to call on her whenever needed; she resides in wooded Dravania, at peace with her books, spells, and beloved witch-wives.

G. DE FAVAGENIEUR

AN INTRIGUE: during the onerous investigation of the erstwhile Guiscareaux, Durremont realized a unique and deep fascination in a young woman on the close peripherals of the lord-vintner's social circle. "GAELLE," an artillery engineer of some modest renown, remains a fixture of Durremont's personal interest. What will come of said interest, few can say—though its ends will likely inspire jealousy from the aforementioned lord-vintner, who also thinks Lady de Favagenieur is quite lovely indeed.

U. DE ROSIERS

A DEVOTION: this man, oft fondly compared to the beasts and scalekin of his native Dravania, is a rare, beloved compatriot of the mademoiselle. In the mild, listless summer following her holy pilgrimage, Durremont was sought out by a woods-witch and tasked to find her son, "ULYSSES." She located him far away in the wastelands of Gyr Abania, where he had been driven to society's very fringes by a dreadful quest of his own. Though the penitent lancer and the heretic warrior made for a (very) unlikely pair, they emerged from their arduous journey stronger, closer—bonded in blood, united in mutual understanding, and tempered by both frost and dragon's flame.

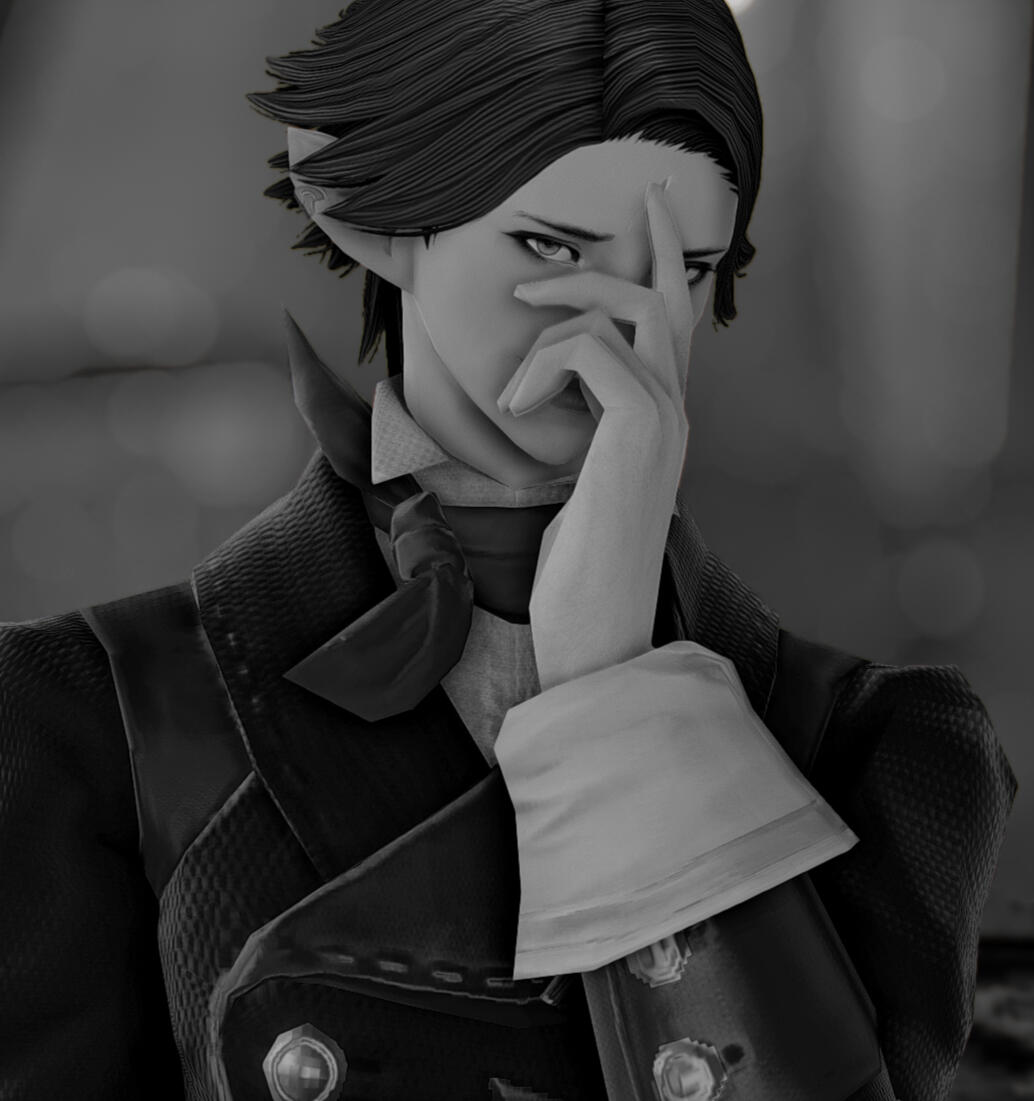

L. DE GUISCAREAUX

AN ANATHEMA: by Tribunal order, Durremont was once tasked with investigation and spiritual examination of Lord "LUCIUS", a vintner and disgraced dragoon. While their initial encounters teemed with animosity, the two forged an unlikely understanding over shared woes and old shame. Durremont won't call Guiscareaux a friend—she has, after all, a rather idiosyncratic definition for the word—but would not deny the truth that the troubled lord-vintner could call upon her lance at any hour, should he need it. (Doubtless, however, that such aide would be delivered with a pointedly scathing remark.)

M. VIRTAN

A COOPERATION: if one can convince the lancer that a certain cause is righteous, they are far more likely to earn her assistance for tasks and toil in support of said cause. How "MJELLE" managed to convince Durremont to step up and join in the efforts to restore the Iron Feast of Dravania is a bit of a mystery; perhaps the enterprising Veena simply knew the right things to say at the right time. While Durremont does not necessarily regard Madame Virtan as either friend or business partner, she does go out of her way to make sure the lady suffers no peril in her many undertakings across Ishgard and Dravania.

E. MARCELLO

A DUTIFUL ALLY: the youngest member of SPEAR, the energetic "ELEANOR" is a fighter who has won a certain fondness from Durremont. Perhaps it is her previous years working with Ishgard's downtrodden youth, or remembrance of fond times teaching at St. Lisieux's convent school for girls—but the lancer sees in Miss Marcello a certain potential towards greatness, physical strength, and good morals. Marking a turn in Durremont's oft-lamented poor accords, she hopes this potential will come to fruition without causing the young woman any harm on the battlefield or the world at large.

F. RIVENSAIL

A COMMONALITY: Following introductions at the hands of Lord de Guiscareaux, Solaine marked a new interest in "FALLON," an Ala Mhigan traveler with a scarlet sense of style. Further encounters proved amicable; though from different parts of the realm, the two are considerably devout to their respective patron gods, and share an enthusiasm for the thrill of adventure. It is notably difficult—either by circumstance or by Durremont's own disaffective nature—for the lancer to make friends, much less see the potential in friends yet to be made. But there is simply something about Miss Rivensail that keeps the lancer curious, and coming around for another cup of coffee.

M. AUVILLIERS

A COMPANION, ONCE: during her earliest weeks at the Lancer's Guild, Durremont was paired for training with a violet-eyed acolyte named "MATHILDE." The proverbial sun to the former inquisitor's sleet, Mathilde soon became Solaine's combat partner and close confidante. Though they have long since parted ways (and may never again cross paths, given the disparity of demands in their respective lives), two facts are certain: Mathilde has witnessed the former inquisitor's rare smile, and, if rumor is to be believed, could make her laugh.

F. LARCHLEG

AN ENDEARMENT: the case of the dead Ishgardian nobleman and the Viera cook falsely incriminated for his murder has long ended, but the acquitted defendant lives on in Durremont's memory as a rare and regarded soul. Though some many moons have passed since their last meeting, Durremont maintains a friendly correspondence with the young mariner. Scrutiny rarely fosters compassion; Halone never defers with mercy—"but I," declares the former inquisitor, "would tear apart this entire room and everyone within it were a finger here lifted against Miss 'FORESTAY.'"

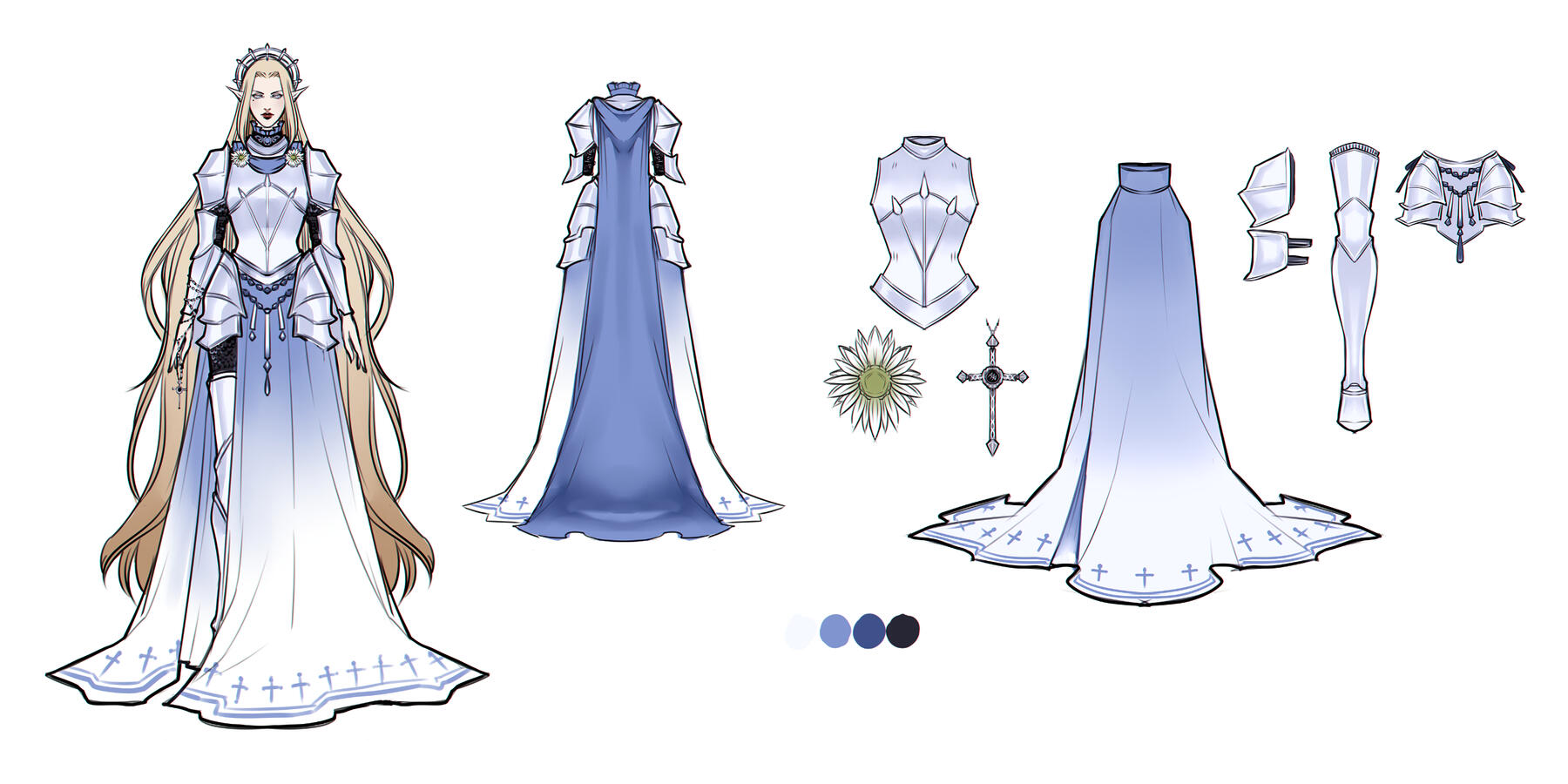

Character Art and Design

Screenshots

Out of Character

⬩ Pacific Time Zone (PDT)

⬩ they/them; writer is 30+

⬩ frequently afkI am a selective, story- and development-driven writer with several years of experience in collaborative RP. If you're interested in writing with me and potential story involvement, feel free to send me a tell in-game.While FFXIV contains fantastical themes/tropes that lean into contemporary parallels (e.g., xenophobia, racism and related stereotypes, class inequality, misogyny, and many others), I will not engage with players or groups whose OOC conduct, character design, or roleplay I find offensive, insensitive, or otherwise unpleasant.DO NOT solicit this character for Ishgard-focused discords or RP communities.

Regarding fancanon: Within this character's backstory are some details reflective of a life and career lived in devotion to the Ishgardian Halonic Orthodoxy. These details (e.g., rituals, saints and prominent figures, scripture, parables, dogma, and other religious minutiae, et. al.) are minutiae inspired by my own personal experience with a similar real-life religion. These details are just "flavor" head-/fan-canon for the purposes of practicing more involved creative writing. None of them are meant to impose on or invalidate any other players' roleplay writing, head-canons, or the in-game lore.

✔️

⚠️

❌

⬩ new connections

⬩ business/mercenary work RP

⬩ exploration and research RP

⬩ training and sparring RP

⬩ slice of life RP

⬩ lore/MSQ-adherent themes

⬩ short/mid-length storylines

⬩ IC conflict and controversy

⬩ LGBTQIA+ characters

⬩ established/backstory connections

⬩ lore/MSQ-relevant NPCs

⬩ WoLs

⬩ venue/event RP

⬩ nobility/political intrigue RP

⬩ Final Fantasy-focused homebrews/fancanons

⬩ excessive headcanoning

⬩ overt "traditional Ishgardian" characters and themes

⬩ shipping/romantic RP

⬩ players & characters under 18

⬩ godmoding, metagaming, and metaposing

⬩ non-Final Fantasy characters

⬩ casual & "meme" characters

⬩ TERFs, use of transphobic terms like "f*ta", and/or any other IC or OOC trans-/homophobia

⬩ poor IC-OOC boundaries & roleplayers who test them

CARRD CREDIT

Layout and design is mine; background image is Papiers de Paris.

Please do not copy or use any assets here unless you have received permission to do so!